Oliver Cromwell’s Disinterment - 30th January 1661

Oliver Cromwell is a name that England is unlikely to ever forget. Cromwell notoriously won the English Civil War, became Lord Protector and acted as the ruler of the Commonwealth of England, Scotland and Ireland. In many people’s eyes, he was a hero of liberty and one of the most significant figures in British history. However, he was simultaneously an enemy of the monarchy. Cromwell successfully upheaved the monarchy and was the main signatory for the execution of King Charles I. This is what sparked the very grisly and very English story of what would happen to Oliver Cromwell’s head years later.

Cromwell had died peacefully from natural causes in his bed in 1656. The Republic had barely outlived its leader as, although succeeded by Cromwell’s son Richard, his weakness as a leader was quickly apparent as nobles had already begun plotting the return of Charles II. After eleven years of Republican Rule, the Monarchy was restored in May 1660. King Charles I’s son, Charles II, returned from exile from the Netherlands arriving in Dover in the Spring of 1660.

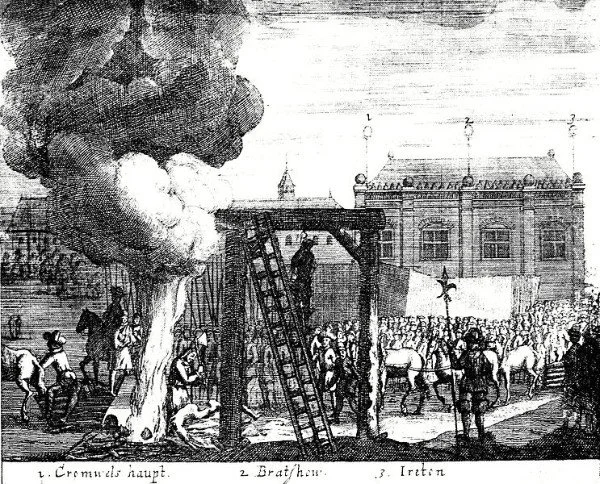

Fuelled by a desire for revenge for his father’s execution, Charles II ordered Oliver Cromwell’s body to be dug up. The dramatic death of Charles I, an execution at the hands of the revolutionaries, spurred on the disinterment. Poignantly, on 30 January 1661, the anniversary of King Charles I’s death, Cromwell’s body was unearthed. The act in itself was macabre and gruesome. This shocking order of disinsertion was a powerful visual and morbid reminder of the success of the monarchy.

Cromwell’s body was made visible to the gawking public eye after being exhumed and dragged to Tyburn, London’s most notorious execution spot. His body was then cut down, decapitated and flung into the gallows in a purposely dug pit. However, the Lord Protector’s head remained on show and was stuck on a pike outside of Westminster, where it remained for many following years, in a manifestation of and physical marker of the monarchy’s power.

In prehistoric times, decapitation was considered the ultimate defeat with archaic people deeming the head as the soldier’s source of wealth and power. The aim of beheading can be split up into three motives: firstly, to kill one’s opponent, secondly, as a war trophy and thirdly to terrify the opponent’s soldiers. It was impossible for Charles II to kill Cromwell, so he took the next best thing: exhuming and then decapitating him for all to see, consolidating his ultimate authority. Oliver Cromwell’s execution and display of his head was a physical symbol to terrify the nation and as an assertion of Charles II’s power and victory over the Republicans, the ultimate message of terror and defeat.

The corpse was hung amongst other members of the Cromwell family, whose graves had also been disturbed in order for these regicides to be displayed. The act of hanging an already dead body up may seem strategically pointless. However, many argue that it altered the memory of Cromwell whilst also dispelling any rumours that he may still be alive, the enduring presence of the corpse recounting the success of the monarchy.

The defeat of the Roundheads and restoration of the Monarchy could not be clearer than if one were to take a snapshot outside of Westminster in January of 1660. The demise of Cromwell and the Parliamentarians was palpable in his post-death execution, a final demonstration of victory and acting as a poignant message that symbolised the King’s newfound power.