The Treaty of Versailles: ‘A Carthaginian peace’?

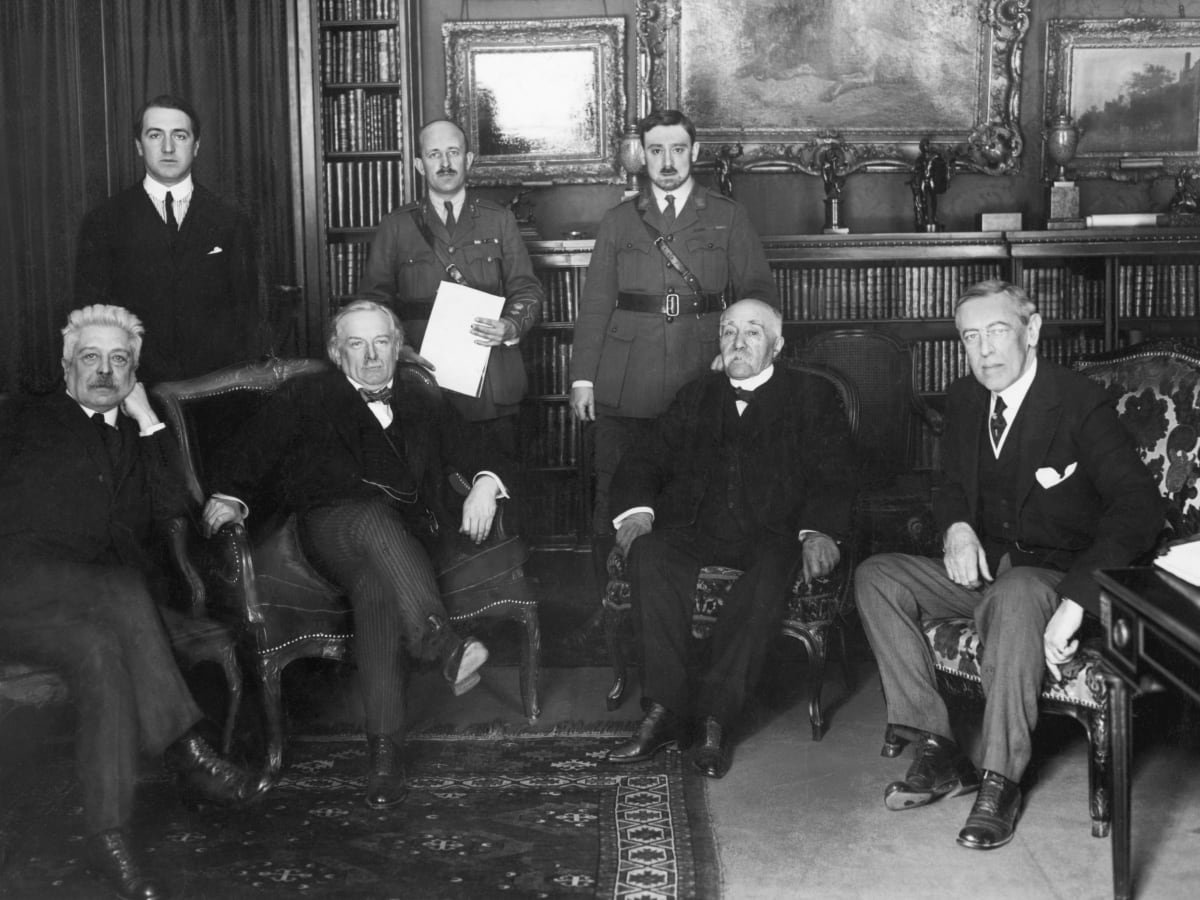

Italian Premier Vittorio Orlando, British Prime Minister David Lloyd George, French Premier Georges Clemenceau & U.S. President Woodrow Wilson meeting at Wilson's Paris home prior to the signing of the Versailles Treaty.

By Mish Al-Roubaie, History Graduate

On this day in 1920, the infamous Treaty of Versailles came into effect, with the intention of providing substantial concessions to manufacture peace after The Great War. Over the past century, the tragic nature of the First World War has been a constant source of remembrance throughout Europe. Yet, beyond the war itself, historiographical interpretations of the Treaty of Versailles have proven to be a recurring point of contention amongst historians, especially those seeking to assess its impact and whether or not the Treaty should be considered a successful resolution to the war.

John Maynard Keynes famously described the Treaty of Versailles as a ‘Carthaginian peace,’ which derives its name from the imposition of ruthless terms of peace designed to completely crush an enemy, such as those that the Roman Republic placed on the Carthaginians after the Punic Wars. Indeed, it’s often argued that the Treaty scapegoated the German people and imposed overly harsh terms on them. In addition to losing 25,000 square miles of land, the treaty limited the German army to a maximum of 100,000 men and forced them to decommission a significant number of personnel and material that could potentially be used in future wars. All of this was in addition to 132 billion gold marks that Germany was forced to pay as reparations, the modern-day equivalent of £284 billion.

Though perhaps harsher than all of this is the treaty’s most notorious article, often referred to as the ‘War Guilt Clause’:

‘The Allied and Associated Governments affirm, and Germany accepts the responsibility of Germany and her allies for causing all the loss and damage to which the Allied and Associated Governments and their nationals have been subjected as a consequence of the war imposed upon them by the aggression of Germany and her allies.’

Across the German political spectrum, this article was widely criticised as a disgraceful violation of national honour. This article is often credited as one of the primary reasons for the popularity of the stab-in-the-back-myth, known as ‘Dolchstoss’ in German, and the eventual emergence of the German Nazi party.

Based on these terms, it’s not difficult to see why Keynes describes the treaty as a ‘Carthaginian peace’ and why so many credit it to the eventual outbreak of the Second World War.

However, recent historiography has been increasingly shifting towards the view that the Versailles treaty was relatively tame in comparison to the other treaties signed at the end of the First World War. In 1918, the German Empire presented the Russians with the Treaty of Brest-Litovsk, effectively breaking up the Russian Empire’s most valuable lands and forcing them to pay huge reparations to Germany. Likewise, the Treaty of Sèvres intended to have huge swaths of the Ottoman Empire’s most valuable lands taken by various European powers.

By comparison, the Treaty of Versailles still left the Germans their most resource-rich lands and didn’t confiscate any significant industrial powerhouses. The reparation payments were high; however, it was only intended that Germany would pay a third of the stated amount in the Treaty regardless. The limits placed on the size of the German military were short-lived. As can be seen with the remilitarisation of Nazi Germany, there were no consequences when these terms were violated.

Assessing the cruelty of the Treaty of Versailles is a polarising discussion in modern historiography because the terms decided at Versailles were successful in creating a feeling of national humiliation in Germany but unsuccessful in doing anything to prevent that humiliation from escalating into another global conflict.

Perhaps the most enduring message of the Treaty of Versailles is not one of cruelty but rather of rash decision-making and half measures, a problem which continues to hinder the resolution of drawn-out and seemingly endless conflicts.